I don’t have a lot of childhood memories, but I vividly remember this one: I’m 10 or 11 years old. I’m standing at the top of the basement stairs, and I’ve just closed the door behind me. I look down into the blackness. There’s a tiny bit of light coming under the door, but it quickly fades as the steps descend. I can’t even see the landing at the bottom.

I feel afraid. Afraid to descend into the darkness. Afraid that, in that moment of vulnerability, that moment of blindness, that maybe, just maybe, all my imaginary monsters would turn out to be real, and would come boiling out of the darkness to consume me.

I stand there for a long time, contemplating that fear. And then, slowly, deliberately, I walk down the stairs, keenly aware of my fear yet consciously choosing to do exactly the thing I’m afraid of. I remember standing at the bottom of the stairs, in the darkness, every sense on high alert. I don’t know how long I actually stood there, but as vivid as the memory is, I think some part of me might be standing there still.

In fact, I’d say that’s true. I’d say some part of me died that day, standing in my dark basement, listening to my breath. The version of me that came back up the stairs was forever changed, in a way I will always remember. I don’t think I realized the significance of it at the time, but I certainly felt the emotion keenly.

I wonder if you have a childhood memory like this, of choosing to face down and overcome an irrational fear. Moments like these are significant in our lives. They are the inflection points through which we grow up.

I see now, today, that I am at a new inflection point. That some fear is preventing me from growing, and that I must confront it by standing right in the middle of it for as long as it takes me to see that it, too, is completely imaginary. I am coming to realize, more and more with each word, that my writing is an attempt to do just that: confront my fear and die to who I am, so that a more grownup version of me can be born.

—

FDR famously said, “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” Those ten words are packed with a remarkable amount of significance. It’s taken a great deal of contemplation for me to understand them—and I’m sure I could contemplate still more, coming to an ever deeper understanding.

What FDR was saying is that the things we’re afraid of are imaginary. 10-year-old Michael’s fear of monsters in the dark? Imaginary. That one’s obvious.

But FDR made this statement in 1933. Wasn’t the Great Depression indeed something real, and not imaginary, to be afraid of? Wasn’t the imminent rise of Nazi fascism in Europe something real, and not imaginary, to be afraid of?

Of course the Depression and Nazis are real. I’m not saying anything so obviously backwards. No, what I’m talking about here is more subtle. Pay Attention.

When we are afraid, we are not afraid of a real thing. We are afraid of our imagined version of what that thing will do to us. We are afraid of what’s going to happen in the future. And the future doesn’t exist, nor do the things we imagine are in it. We make them up. And then, often, we become afraid of them.

So young Michael wasn’t afraid of the dark. He was afraid of the monsters he imagined were in the dark, and what they would do to him if they caught him. Similarly, the world wasn’t afraid of the Great Depression. They were afraid of the hard times and starvation they imagined were coming for them. And free people weren’t afraid of Nazism. They were afraid of what the Nazis would do to their loved ones, their countries, and the world. But all those fears have one thing in common: they were about the future. And the thing about the future is that it has yet to be written—and being afraid of it doesn’t give us anything in terms of helping to write a good version of it.

For instance, when young me was standing at the top of the stairs ruminating on the darkness, he was afraid. But instead of wallowing in the fear, instead of letting it control his actions, he did something about it. He took control of the future he was afraid of. Because once he descended into the blackness, the fear disappeared, replaced by a more immediate concern: the need to pay close Attention, to be completely in the moment, to listen for the scrape of claws or slither of a tentacle, to feel outwards as if through sheer effort he could expand his sense of touch beyond his skin, to be open to the slightest smell that indicated danger.

In that moment, Michael was not afraid. No. In that moment, there was no room for fear. There was only room for being alert. For being activated. For being in the present moment.

And that kind of a moment is something we rarely experience in today’s world, precisely because we’re afraid of it. Yet, ironically, my experience that day in the basement taught me the first part of a lesson I’m still trying to realize today: that being in the moment doesn’t just temporarily push the fear aside. It actually disabuses you of the unreal notion of the thing you’re afraid of. There were no monsters in the darkness, waiting to get me.

But, again, I can hear you asking (and part of me is still badgering myself about this): aren’t I making a false comparison here? Wasn’t the job loss, deprivation, and starvation of the Great Depression something real?

Yes, of course it was. And I’m not trying to ignore or diminish the suffering people went through during those years. As I said, I’m trying to point to something more subtle. The world is more complicated than we know, and it’s good to try to look at it from multiple, seemingly-contradictory perspectives. Doing so forces us to stretch ourselves, and stretching causes us to grow. And growing (up) is precisely what we’re talking about here.

The point is not that the Depression wasn’t real, or that job loss, deprivation, or starvation aren’t real. The point is that when you’re starving, you aren’t afraid of starving. You’re simply trying to solve the problem. That, or you’ve given up. And both possibilities are—just like the experience of standing in the darkness—all-consuming. There is no room for fear when you’re starving, because it gets in the way of solving the problem, or because you’re too exhausted to care. In other words, fear is a privilege we exercise when we feel safe. And we exercise it precisely because we are uncomfortable feeling safe. (Which, now that I think about it, makes sense, because I think feeling safe is imaginary in exactly the same way fear is.)

And, finally, I think the reason we are uncomfortable feeling safe is because we realize that when we are out there taking action, trying to make the world a better place, we don’t feel safe. Feeling safe is a sign that we’re being complacent.

So, to sum up in other words: fear is a symptom of safety. If you want to be less afraid (and I both hope you do and think you should), then pick one of your fears, descend to the dark basement, and face it. Almost none of the things we’re afraid of in today’s world will actually hurt or kill us. Just like my monsters in the darkness.

Here, I’ll go first.

—

At first, when my memory of overcoming my fear of the darkness came back to me, I didn’t know why. I figured it was just some random whim of childhood memory. But in the writing of this piece I’ve come to realize that it came back to teach me something: all these years later and I’m still afraid. Not of the same thing as when I was 10. Not of the dark. But it’s still the same fear. The fear of something imaginary. Of something I have never seen, and believe on some level I will never see: death.

I recently re-encountered a Paul Simon song whose lyrics touched me deeply. (Listen here, if you like.)

Through the corridors of sleep, past shadows dark and deep

My mind dances and leaps in confusion.

I don’t know what is real, I can’t touch what I feel

And I hide behind the shield of my illusion.

So I’ll continue to continue to pretend my life will never end

and flowers never bend with the rainfall.

The mirror on my wall casts an image dark and small

But I’m not sure at all it’s my reflection.

I’m blinded by the light of God and truth and right

And I wander in the night without direction.

So I’ll continue to continue to pretend my life will never end

and flowers never bend with the rainfall.

No matter if you’re born to play the king or pawn

For the line is thinly drawn ‘tween joy and sorrow.

So my fantasy becomes reality

And I must be what I must be and face tomorrow.

So I’ll continue to continue to pretend my life will never end

and flowers never bend with the rainfall.

I’ve listened to that song dozens of times over the last few days. I cried almost every time, at first. For some reason, the song plucks at my sadness like Paul Simon plucks his guitar strings. But as I’ve come to know it better—to learn the lyrics and be able to anticipate them as I listen—it slowly becomes less and less of an emotional hammerblow for me to listen. It’s as if, in taking the song into myself, I become somehow inoculated against whatever sadness I feel there. It’s not gone. Not entirely. But I have become better at engaging with the feeling, and thus better at engaging with the song. I can use it, now, to examine the source of the feeling without being overwhelmed.

It’s the same as standing in the darkness to overcome a fear of the darkness. In every moment of feeling, we have a choice: we can merely feel our feelings (fear, sadness, etc), or we can let them lead us to a place of deeper understanding. And that’s what I’m advocating for, and trying to demonstrate.

So what is beneath the sadness this song provokes in me? What understanding have I gained? It’s this: Someday I’ll be dead. Someday you will be, too. The same goes for my parents, my wife, my friends, and my daughter. It’s true of everyone.

I grieve for us. That, at least, feels generous of me. To be sad that someday we won’t exist any longer. I’m sad because I love my family, and my friends, and you, too, reader. I’m sad because I love that little boy I used to be, who was afraid of those monsters in the dark.

But I’m also afraid. And that feels less generous, more selfish. Oh, it’s understandable, certainly. I’m not ashamed of my fear. But I am aware that it doesn’t serve me. In fact, writing these words right now, I can feel my fear trying to justify itself. I can hear the rationalization: “I’m trying to keep you safe.” And that’s actually true. Like any good deception, it has a lot of truth to it. The problem is, there’s no safety from death. Nothing I can do will make me immune to it. Maybe it’s the same as the monsters of my youth, in that nothing I could do would make me immune from them, either, because they weren’t real.

So… am I saying death isn’t real? I don’t think so. Not quite. That’s too close to the eternal paradises religions describe to us, and that story doesn’t ring true to me. Well then, what does ring true? I’m not sure. Thinking about how to write it, I actually feel… silly. Like, I don’t know what death is. I don’t even know what it’s like. Certainly not from the inside (so to speak). What will it be like to not exist? Do we even not exist after we die? How could we ever know that? Silly Michael, afraid of something he doesn’t understand, can’t describe, and has never experienced. I guess that’s just fear, though; it’s always about the person or thing we haven’t met.

I’m having trouble, I think, because I’m trying to write about something to which there’s no rational angle of approach. Death is beyond reason. Nonexistence is beyond reason. So what good will words do us here? Unless they can put us in a state of mind beyond words. Something like the old Zen koans: questions without answers, that get us to open ourselves up to whatever reason-transcending possibilities exist in reality.

And here’s the question I find myself asking: what is the opposite of memory? When I’m thinking about being alive (in an attempt to think about being dead), what am I doing? I’m thinking about memories using words (which themselves are memories).

And what happens when I stop using words?

Well… nothing. Nothing bad happens. The world just keeps moving along. And those moments of movement are happening across the universe, throughout all of reality, and they encompass everything that is. So, nothing happens… and also everything happens. Maybe that’s death. Nothing, and everything.

It doesn’t seem useful to be afraid of everything. And it certainly doesn’t make sense to be afraid of nothing.

Still, that’s only a rational answer. Even if it’s the best I can give right now, it won’t get me all the way to the other side of my fear. It’s just one step down the stairs. To go further will require hard emotional work—the same hard emotional work I did when I was 10 (which I clearly still remember to this day). I can do that work now, while I’m alive, or I can wait until I die and have it done for me. There’s no better or worse to it, no right or wrong. All I can do is follow the path I’m given. So that’s what I’ll continue to do.

—

Ok, I’ll pass the ball back to you here. What was that like for you? To witness someone doing his best to stand in the middle of his fear? Did it sound difficult?

How did it feel? What did you notice happening in your body as you were reading? Whatever it was, it’s ok. There’s nothing wrong with any feeling. They rise and fall in us, like waves. All they ask is to be noticed, felt, and allowed to pass on. But they do have something to tell us. What are you feelings telling you right now?

It seems to me there must not be any right or wrong way to go about being you. You like what you like, you’re afraid of what you’re afraid of, and that’s that. There’s no sense in trying to change any of it, any more than there’s any sense in trying to convince a rock to change color. A zebra can’t change it’s stripes, they say. So when you just sit, and pay Attention, what are you like? Who is the You that shows up? And what feelings is that You clinging to, and what feelings is it hiding from?

The answers to those questions may or may not surprise you. I don’t know. It seems safe to assume you approach these things differently than I do. And even though I don’t think there’s any right or wrong way to approach them (because I suspect that for you, same as for me, the only options are to do the work or have it done for you when you die), I hope you will choose to seek answers to the questions of who you are, what you’re doing here, and why you matter.

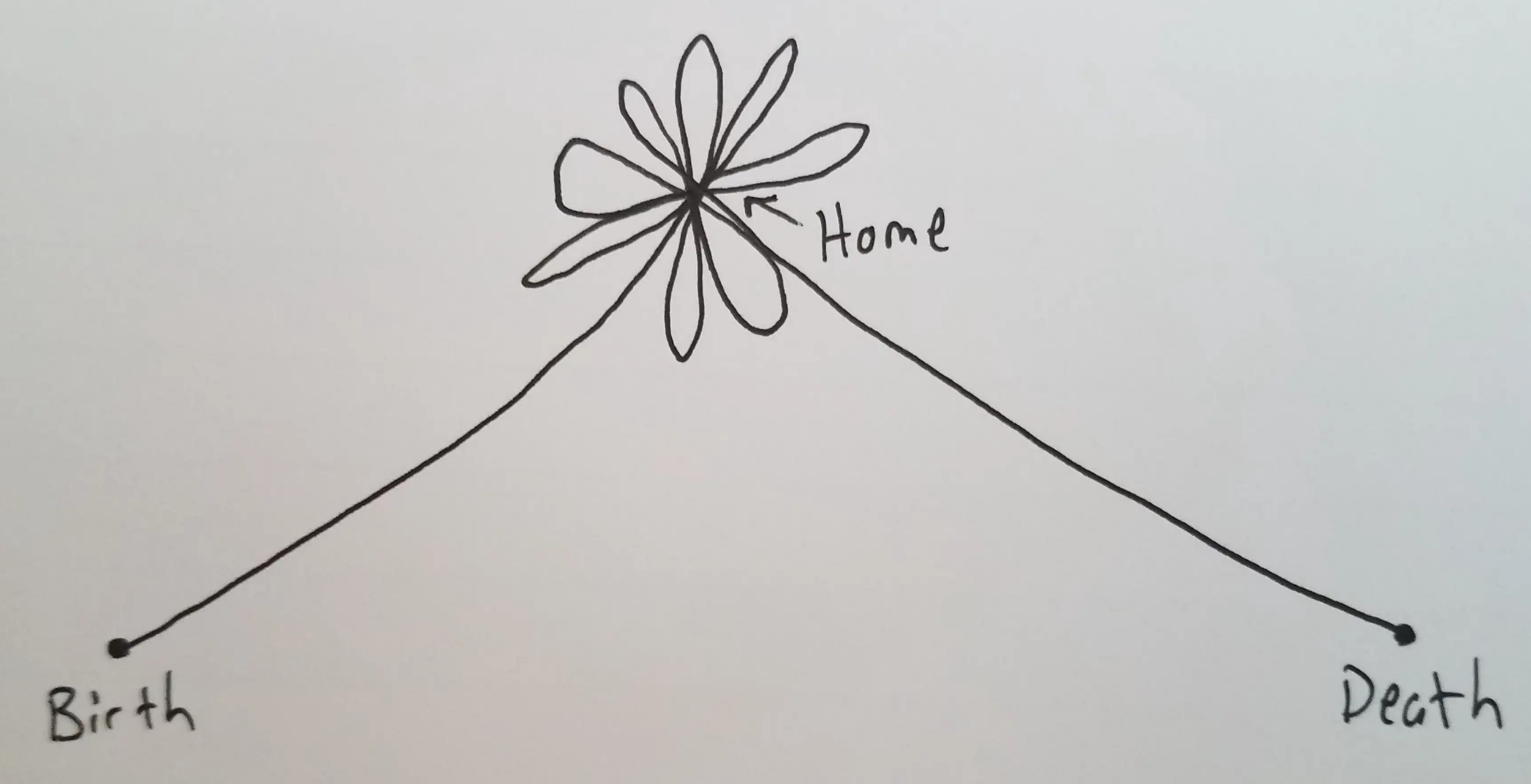

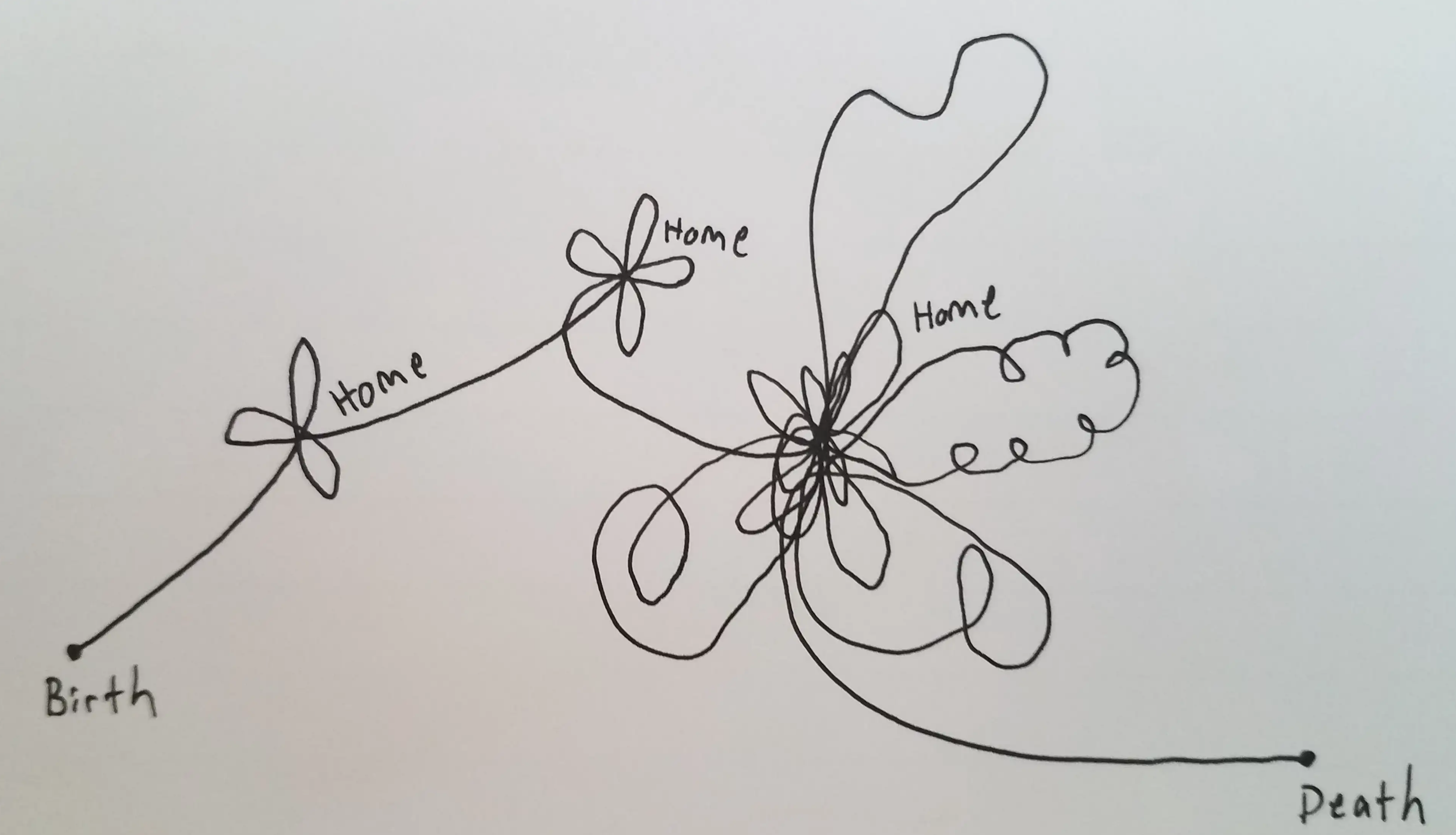

The thing about these questions is that the answers, like feelings, are always changing. When I was 10, I needed to stand in the darkness for a while in order to be who I was and become who I was becoming. Now that I’m older, I need to write. Different answers to the same questions, that we must continue to pursue if we’re to continue to grow up.

So. To answer the question in the title of this blog post: “why not fear?” After all this, I think there is no solid reason, other than that I don’t want to. I’m tired of being afraid. It doesn’t do me any good that I can see. So it’s time to let go of it.

And, finally, what about you? If fear still serves you, that’s fine. Maybe there’s something else in your life, something you want to get over and move past, but you’re afraid to. If you take one thing away from reading these words, make it this: if you want something, that’s enough reason to pursue it. And if you want to be rid of something, that’s enough reason to leave it behind. Just be honest with yourself. Be compassionate to yourself. When it’s your time to do whatever it’s been given you to do, you’ll do it. I know you will. Because I love you, and you love you, and love is the reason everything ever happens.

I hope you continue to happen.